The weirdest food Russian tsars ate

1. Roasted swans – the Moscow tsars’ favorite

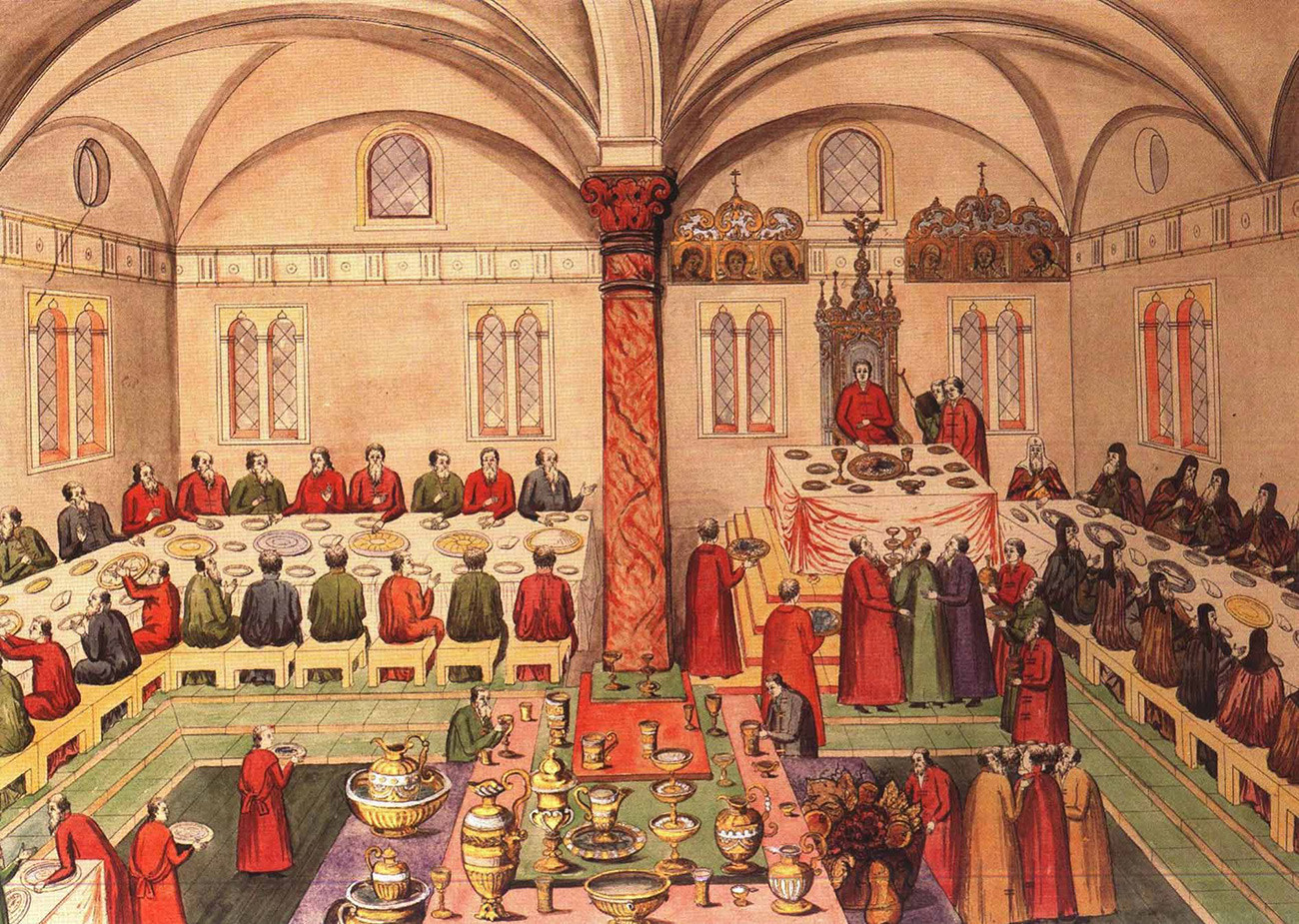

The feast of Ivan the Terrible in his 'Alexandrova Sloboda' residence.

Yuri SergeevWhen Sigismund von Herberstein, an ambassador for Austria in Russia, came to the court of Moscow’s Grand Prince Vasiliy III in 1526, he was invited to an honorary feast, where he first saw roasted swans, a dish Moscow rulers boasted of.

Herberstein wrote: “The servers first brought in brandy, which [Russians] always drink at the commencement of the dinner; then they brought in roasted swans, which it is their custom to lay before the guests for the first dish, whenever they eat meat. Three of these being placed before the prince, he pierced them with his knife to try which was the best, and which he would choose in preference to the rest, and immediately ordered them to be taken away. The servers placed the swans, after they had been cut up and divided into parts, in smaller dishes…”

Sigismund von Herberstein (1486-1566)

Public domainHerberstein notes that when eating the swan meat, Russians used a sauce made from vinegar, salt, and pepper. Swans were considered food fit for a tsar. So, if the guests were not noble and important enough, no roasted swans were served to them. Meanwhile, this dish was on the tsar’s personal table at every major feast. Swans were often served with their beaks covered with sheet gold.

But the secret to preparing roasted swans was lost in time. In the 19th century, Sergey Aksakov, a writer and a huntsman, wrote: “I don’t understand why swans were considered delicious and honorary food with our Grand Princes and Tsars. In those times, they must have known a better way to make its meat soft.”

The tsar's feast at the Palace of Facets in the Moscow Kremiln, 1673

Public domainThe roasted swans were supposedly marinated in vinegar and/or sour milk, and then prepared in a Russian stove – only steady warming, without roasting on an open fire, could make the bird’s meat juicy. But that recipe is now lost.

2. Tel’noe – meat made of... fish!

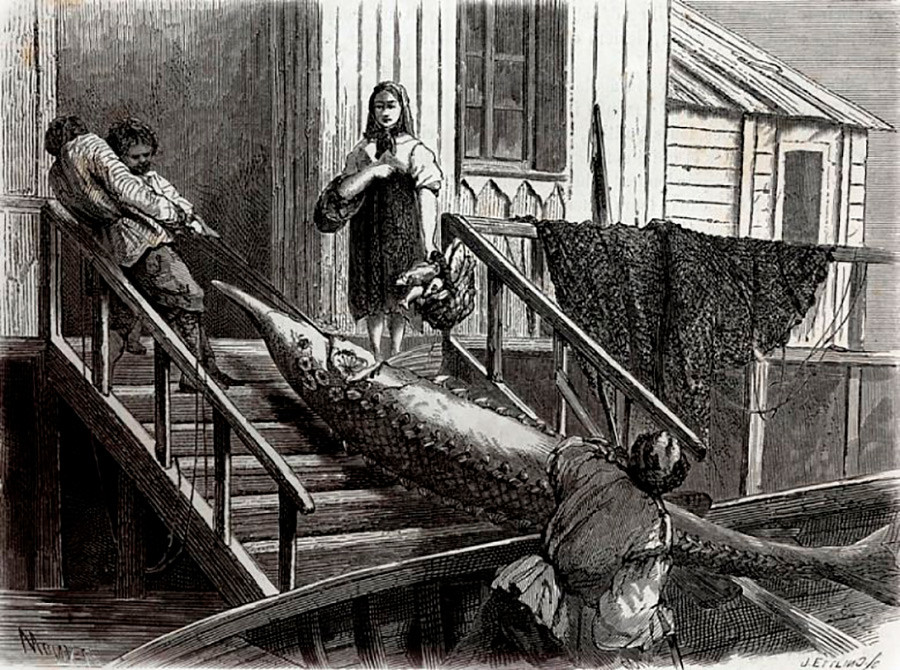

A giant sturgeon

E. MeyerFor 200 days a year, Russian Orthodox believers would hold fast. The tsars and the Grand Princes also observed it, as all Russians did. But when a feast in the tsar’s palace – for example, his tsarina’s name day, or the coronation’s anniversary – would fall on a fasting day, what ‘elite’ dishes would there be instead of meat, which was forbidden during the fast? Well, Russians learned to make meat from fish. It was called tel’noe – “one resembling a body”, if translated from Russian.

Here’s how Paul, the Archdeacon of Aleppo, who visited Moscow in 1654-1656, described tel’noe: “Taking out all bones from a fish, they crush it in mortars, until it becomes like dough, then add onions and saffron, put it into wooden forms shaped like lambs and baby geese, and boil it in vegetable oil in deep well-like pans, to roast it completely… The taste is excellent – one can easily take it for real lamb meat.” In 1678, Czech traveler Bernhard Tanner wrote that “the art of Moscow cooks can transform fish into roosters, chicken, geese, and ducks, by making the fish look like these animals.” Russian food historians Olga and Pavel Syutkin didn’t find similar dishes in any other cuisine of the world, so it’s a unique Russian dish.

3. Botvin’ya – a poor man’s soup that the Emperor liked

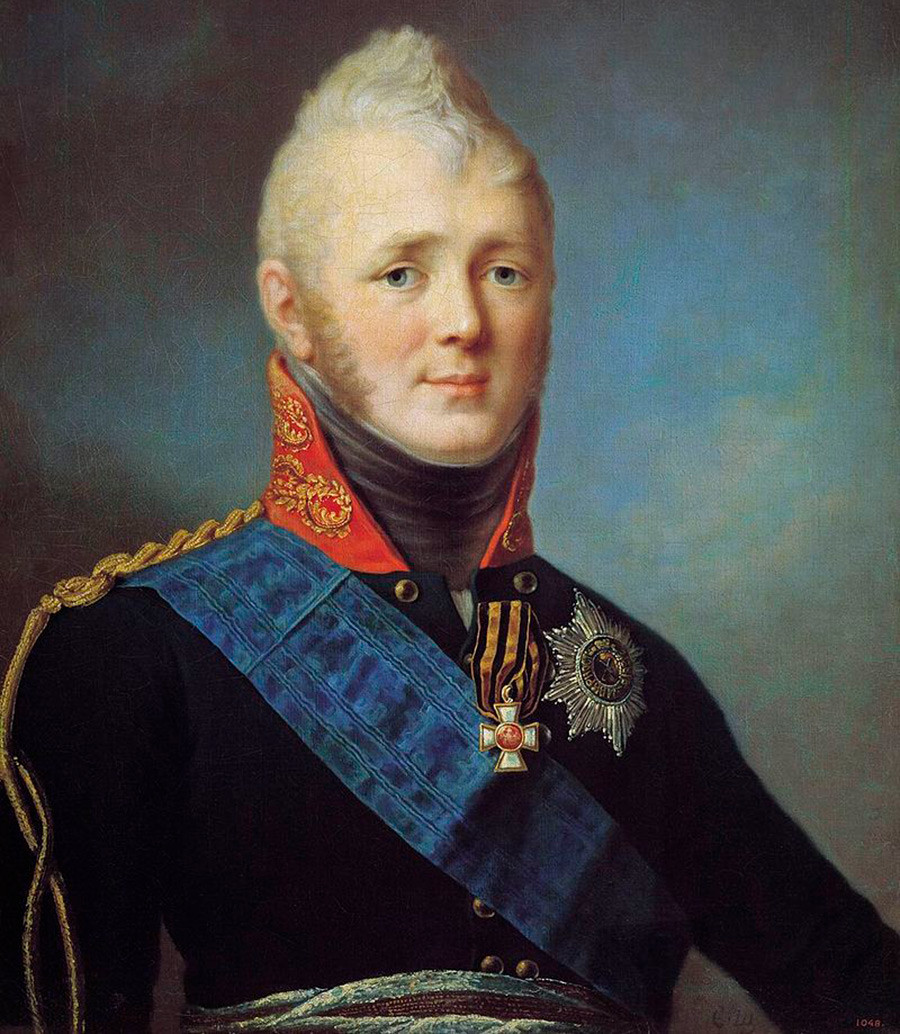

Alexander I of Russia (1777-1825)

Stepan SchukinEmperor Alexander I of Russia (ruler of Russia from 1801 to 1825) was German by blood and brought up in the finest royal manner by his grandmother, Catherine the Great, also of German descent. But what Alexander inherited from his grandma was the love for Russia – and its cuisine. Alexander’s favorite dish was botvin’ya – the cheapest vegetable soup that every Russian woman knew how to cook.

Botvin’ya was a cold summer soup. Its name is derived from ‘botva’ – or ‘vegetable tops’ in Russian, and it was mainly made out of beetroot leaves. Beetroot, spinach, and sorrel leaves were boiled for 1-2 minutes, then chopped together with pickles, dill, and green onions. Then it was all covered with white kvass that was used as broth. White fish (sturgeon) was then usually served together with botvin’ya.

Botvin'ya

Legion MediaThere is a funny story about Alexander and botvin’ya. Alexander was very friendly with the English ambassador and, once, while talking about Russian cuisine, the Emperor noted that the ambassador had never tried botvin’ya. Subsequently, as soon as botvin’ya was served once more to the tsar, Alexander ordered a portion to be sent to the ambassador. But the ambassador’s cook didn’t know the soup was meant to be served cold and heated it up before serving. The following time the Emperor saw the ambassador, he asked how he liked Alexander’s favorite soup. The ambassador, who, by that time, already understood his cook’s mistake, answered politely: “A dish that was heated surely can’t be as good as when it had been just prepared.”

4. Salted watermelons, plums, and… tea with cucumbers

Salted watermelon

Legion MediaThe Russian climate is mostly cold, and our ancestors, who didn’t have refrigerators, could enjoy fresh fruit and vegetables for only about 4 months every year. So it was usual to preserve food by salting and marinating it. Everybody’s familiar with salted cucumbers (pickles), a staple Russian food.

But there were also salted watermelons and even salted plums on Russian tsar’s tables. Since the times of Alexis of Russia (1629-1676), watermelons were grown in Astrakhan and brought to the tsar’s table. Alexis tried to grow watermelons in Moscow, but they weren’t good enough.

But watermelons were not salted to preserve them for the cold months, but because the Orthodox Church prohibited eating fresh watermelons. The reason for that was… their resemblance to the severed head of John the Baptist! So watermelons were marinated in honey with garlic and salt, and they still tasted good. Salted plums were another similarly intricate dish.

But Emperor Nicholas I definitely took the cake with his culinary tastes. Nicholas didn’t eat anything sweet – but with tea, he preferred crunchy salted cucumbers (pickles) and was the only one in his family who loved this oxymoron of taste.

5. Unicorn’s horn and bear’s liver

The narwhal (Monodon monoceros), or narwhale, is a medium-sized toothed whale that possesses a large "tusk" from a protruding canine tooth.

Dr. Kristin Laidre, Polar Science Center, UW NOAA/OAR/OERRussian tsars before Peter the Great were as superstitious as their subjects, and, in the absence of medical science, believed in healing potions, including the one made out of “unicorn’s horn”. Wait, what? Unicorns existed in Russia?

Powder made out of “unicorn’s horn” was believed to be a universal cure: it alleviated all diseases and was considered a multi-purpose antidote. In the 17th century, unicorn horn powder cost more than the same weight in gold! Tsars and noblemen used to dissolve the powder in drinks and ingest it. But what was the “unicorn’s horn” really? Supposedly, crafty witch doctors of the 17th century had obtained narwhal whale’s tusks that looked exactly like the fabled unicorn horns and made fortunes on them.

Alexander II of Russia talking to the peasants during the hunt

Klavdiy LebedevAnother unbelievable dish of Russian tsars was bear’s liver that Alexander II (ruler of Russia from 1855 to 1881) loved. An avid huntsman, Alexander was firmly against ‘prepared’ hunts, when the prey was already herded into a specific area in the woods, so it could be hunted down easily. Alexander preferred embarking on real hunts, sometimes searching for prey for days. And he loved eating what he shot right away in the woods. During those hunting days, Alexander loved to drop the ceremonies and eat bear’s meat or a bear’s liver roasted on an open fire – a delicacy few people would even find edible, and even fewer – tasty. These days, bear’s liver is considered toxic because it has levels of vitamin A that are dangerous for humans. But Alexander II could easily bear this, it seems!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox