"Vasilisa Prekrasnaya" by Ivan Bilibin. In this picture, we see a Russian witch: she has one braid, which means she wasn't married, her hair isn't covered, which means she transcends the traditions, and she has a lit-up human skull on a stick, wonder what is it for?

Ivan Bilibin/Public DomainWitch in Russian is NOT Baba Yaga. Russian witch is called ved’ma – the one who possesses secret knowledge. In pre-Petrine Russia, a witch, a female sorcerer (знахарка, znakharka), was a necessary member of the society. Witches dealt with healing and spoilage, as well as spells for brides and grooms, predictions of the future with fortune-telling books – in general, they did all things that people turn to tarot and folk healers for these days. The only difference was that, in the 17th century, people could be whipped for this kind of treatment or even burnt in a wooden house.

A hut in a winter forest, by Alexey Savrasov, 1888

Public DomainIn villages, a woman could earn a reputation of a witch because of a “wrong life”, in the opinion of society. “The women who deviated from the usual path of life, associated primarily with the implementation of family roles, could gain a status of witches,” writes ethnographer Tatiana Sczepanskaya in an article about witches for the encyclopedia ‘Muzhiki and baby: Male and female in Russian traditional culture’. Prostovoloski, that is, girls who had sinned before marriage, samokrutki, who married of their own free will, without parents, vekovukhi (who did not marry at all) – such women were more likely to attract suspicions of practicing witchcraft.

Keith Thomas in his article ‘Religion and the Decline of Magic’ suggests that solitary living women, who often needed domestic help, were the most vulnerable and, in order to have a reason to refuse them, they were “declared” witches and hounded away. Of course, there were also women who made money using witchcraft on purpose.

Witches in Russia, however, were not always unmarried. The book by Nicholas Novombergsky ‘Witchcraft in Moscow Tsardom in the 17th century’ indicates the marital status of some urban witches – they were wives of a deacon, a gunman, a dragoon, a “stray man”, a strelets, a soldier-mercenary. Most of them belonged to the lowest, powerless estates: serfs, peasants, foreigners (the Tatars and “Circassians”).

In general, Russian witches and witchers were usually very poor. Witchcraft services cost mere kopecks and many of the witches we know from sources generally lived on handouts. “Witchcraft was the weapon of the weak and helpless,” writes Nada Boszkowska, one of the foremost historians of the Russian women. “Women used the fear of witchcraft spells to frighten those who were more powerful and stronger.”

And, indeed, they did. In Bolkhov in 1627, Anna, a strelets’ wife, threatened an official with spoilage. And the rebellion of Stenka Razin brought fame to Anna of Arzamas (Temnikova), a peasant witch, who made spoilage and passed her art to others.

The rite of 'plowing,' 19th century

Public domainRussian sources do not mention witches doing pure evil – they do not send hail or bad weather, do not summon the devil and do not make human sacrifices. So why did Russian society turn to witches? For ritual functions, folk medicine and even… investigative theft.

Village witches, as well as widows and single women, took part in different rites left from pagan times. For example, in the rite of “ploughing”, which protected the village animals from “cow death”, that is simply the loss of livestock. Widows and unmarried women were absolutely necessary for this rite.

In circumstances where there was no medical care, it was the witches and znakharkas who could help with toothaches, hernias, “black afflictions” (aka epilepsy) and other, popular ailments. In 1642, one streltsy gave a woman a witch’s written spell against “black affliction”. Widow Ulita Shchipanova from Vologda Region learned healing from her mother and had a stock of roots and stones for all diseases, including lice.

Of course, since witches could heal, they also sent disease and spoilage. In the village, witches were most often accused of inflicting hiccups, hysterical fits, “dryness” (paresis of different kinds) and male impotence. Luring brides and grooms was also an entirely witchcraft field of knowledge.

The robbed, deceived, people with the problems at work – they all turned to witches, because minor conflicts between peasants did not interest the official executive power and whom could a poor man ask for help? In 1647 in Moscow, a peasant by the name of Simon was robbed and he went to a sorceress named Daryitsa for help, who then pointed out the culprit. In 1658, a peasant woman in the village of Lukh acquired some magic salt and scattered it in order to release her husband from prison. Moscow sorcerers “sold” incantations for successful trading and one sorcerer was recorded as recommending: “Bury a severed bear’s head in the middle of the yard and the cattle will breed abundantly.” (Do NOT try this at your farm!)

"Znakharka" by Firs Zhuravlev

Kaluga Oblast Art Museum/Public domainIn Russia, it was believed that one could become a witch – not through contact with the devil, but through communication with otherworldly creatures. According to Tatyana Sczepanskaya, a girl from Novgorod Region, abandoned by her groom, had a dream about a sorcerer bear, who revealed to her the secret knowledge. The girl became a famous healer in the Okulovo district. The gift she received was the result of a connection with an otherworldly patron who “replaced” her groom and put a new meaning in her life – witchcraft.

It was possible to receive a patron demon or secret power from another sorcerer or witch, for example, at the time of their death. In the Novgorod Region, there are stories of “fire serpents”. One could create such a serpent by finding a “cock’s egg” (an undeveloped, soft chicken egg the size of a quail egg) and carrying it under one’s arm for two weeks, while keeping a vow of silence. It was believed that a flying serpent would hatch from such an egg and would bring the milk from other people’s cows to the hostess – all she had to do was to put empty pots and jars on the window sill at night.

The search for witches was usually associated with crises in village life. Droughts, epidemics and epizootics, as well as paralysis and hernias among peasants – all this made one desperate to look for someone to blame.

A witch was supposedly the easiest to catch if she was caught performing a ritual. Witches would make zaloms (‘knots’) out of rye or wheat in the fields at dawn, walk in the dew with hair loose and drag a tablecloth behind them to collect dew that symbolized stealing milk from the cows. Of course, nobody could really catch them doing this.

It was believed that a witch could turn into an animal – a cat, a dog, a pig. Sometimes, one would catch an ownerless animal and leave a mark on it – a cut on its ear or muzzle. If the suspected person then became ill or showed calamities in the face or ears, the “guilt” was proven.

READ MORE: How women ran business empires in Tsarist Russia

Village women, in general, checked if a light in the lonely woman’s house was on at night – “it is a serpent visiting her”. If children born out of wedlock appeared, it was “she bore a devil’s child”. If an old woman “wasn’t touched by death” – that was an occasion to ask her whom she bewitched and whom she did harm, because it was considered that witches were not sent to the other world for their sins. It was also possible to help a witch to be reposed by “taking” her power and knowledge.

A “proven” witch was not only avoided, but could also be punished. First of all, she was not allowed to enter anyone’s house, she was refused such basics as salt, matches, flour. Peasants could set fire to the witch’s house or to the witch herself. In the late 19th century in Poshekhonsky County, Yaroslavl Province, peasants suspected an old woman of witchcraft after the death of livestock and tried to burn her in a log cabin. Only a priest saved the woman.

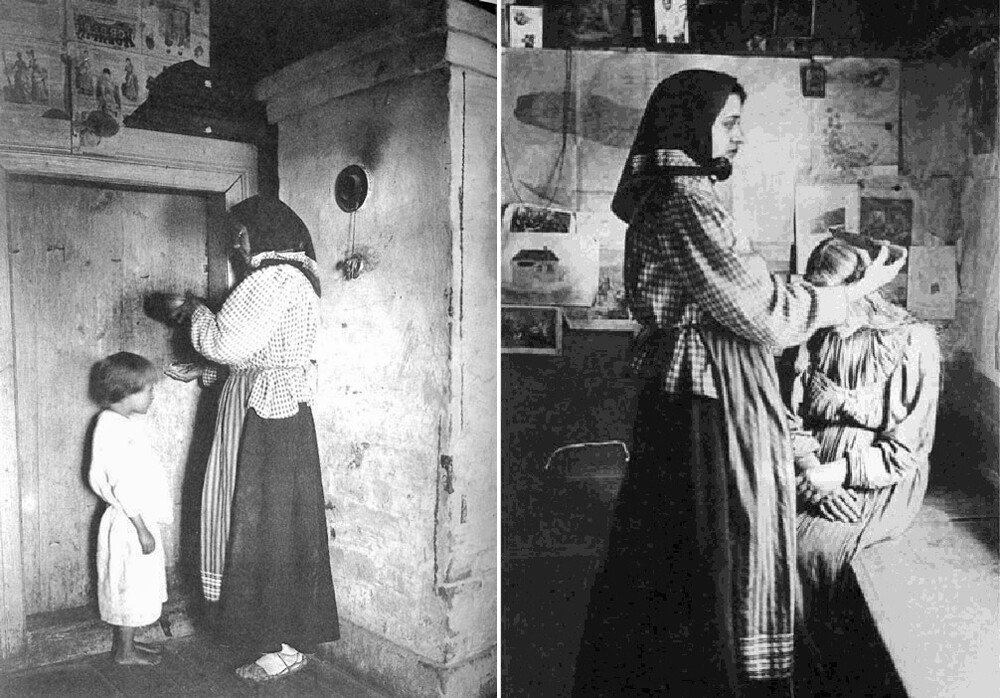

A znakharka healing a child and a woman. Ryazan region, 1914

Public DomainIn general, in Russia, execution for witchcraft was not a frequent occurrence. Of the 99 cases of witchcraft in Moscow between 1622-1700, only 10 ended in death by burning. Still, if executions by fire occurred, they were performed not by tying the executed ones to a pillar, but placing them in a log cabin – the same way they burned the Old Believers in Russia. Russian sources have also preserved no information that Russian witches ever gathered together. “The papers do not mention Russian witches’ collective flights or any kind of coven,” writes Nada Boszkowska.

Russians had ways of “detecting” witches, but there were no “tests” like immersion in water or weighing nor looking for devil symbols or signs on the body. Russian witch doctors and witches were indeed tortured on the rack, but, back then, it was one of the most common methods of inquiry in any criminal case. In general, as Boszkowska writes: “In the Moscow Tsardom’s laws, witchcraft remained only a way of inflicting bodily harm” – this referring primarily to spoilage. Punishments for most witchcraft cases did not differ from other penalties in criminal cases. Executions by lashes, whips, exile to Siberia – that is what awaited most of those accused of witchcraft.

An important difference was also the fact that in Russia witchcraft was not solely a woman’s affair. There were always fewer women accused of witchcraft than men. Witchcraft historian professor Valerie Ann Kivelson examined 223 Russian witchcraft trials in the 17th century. Of the 495 accused in them, 367 (74 percent) were men and only 128 (26 percent) were women.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are constantly under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox