At the end of 1724, Peter the Great, who was already severely ill with bladder and kidney diseases, departed to inspect the Ladoga Canal – more than 100 kilometers along Lake Ladoga. His court physician insisted that the tsar refrained from this journey, yet Tsar Peter remained adamant. The project was crucial; the canal should have tremendously increased trade volumes with Europe. Besides, by fall, the tsar’s health seemed to have improved.

Time has shown, however, that this was a fatal mistake.

Wading in sea water in cold, bad weather (at Lakhta, Peter the Great, waist-deep in ice-cold water, had to rescue a ship aground with soldiers) only exacerbated the bouts of his sickness. Soon enough, the 52-year-old tsar became bedridden. His condition worsened so quickly that he couldn’t write his will: according to witnesses, he was only able to utter “Leave all to…” before he lost consciousness.

The tsar died on February 8, 1725, in a small room in the Winter Palace – so cramped that the tsar’s coffin (216 centimeters long to match Peter’s height) barely fit into it. But, although his death was quite sudden, Peter had been preparing for his funeral his entire life.

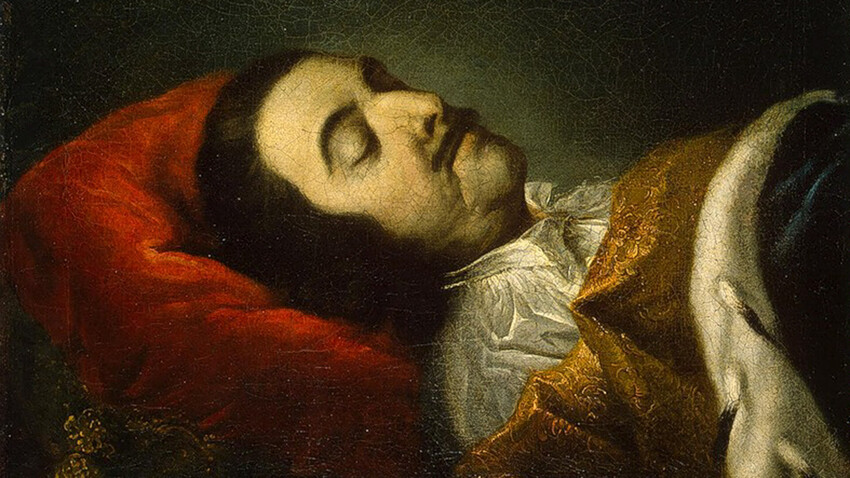

Death Of Peter The Great

Legion MediaFor that, he had changed the rules of royal funerals and became the first Russian ruler to be buried with a new ceremony. Peter, opposed to many old Russian traditions, didn’t want to be buried the same way Moscow tsars were – on the next day after his death. He wished for pompous and lengthy funerals like those of European kings. And he learned from experience. He sought to attend all funerals of noble foreigners in the Russian service and himself participated (financially, as well) in the organization and conducting of funeral rites. Back in 1723, he ordered Russian diplomats to send him detailed descriptions of the funerals they had the chance to attend overseas. It was obvious that Peter the Great was seemingly “rehearsing” the funeral ceremony he was preparing for himself – taking example from, first of all, French kings.

Portrait of Peter the Great on his Death-Bed

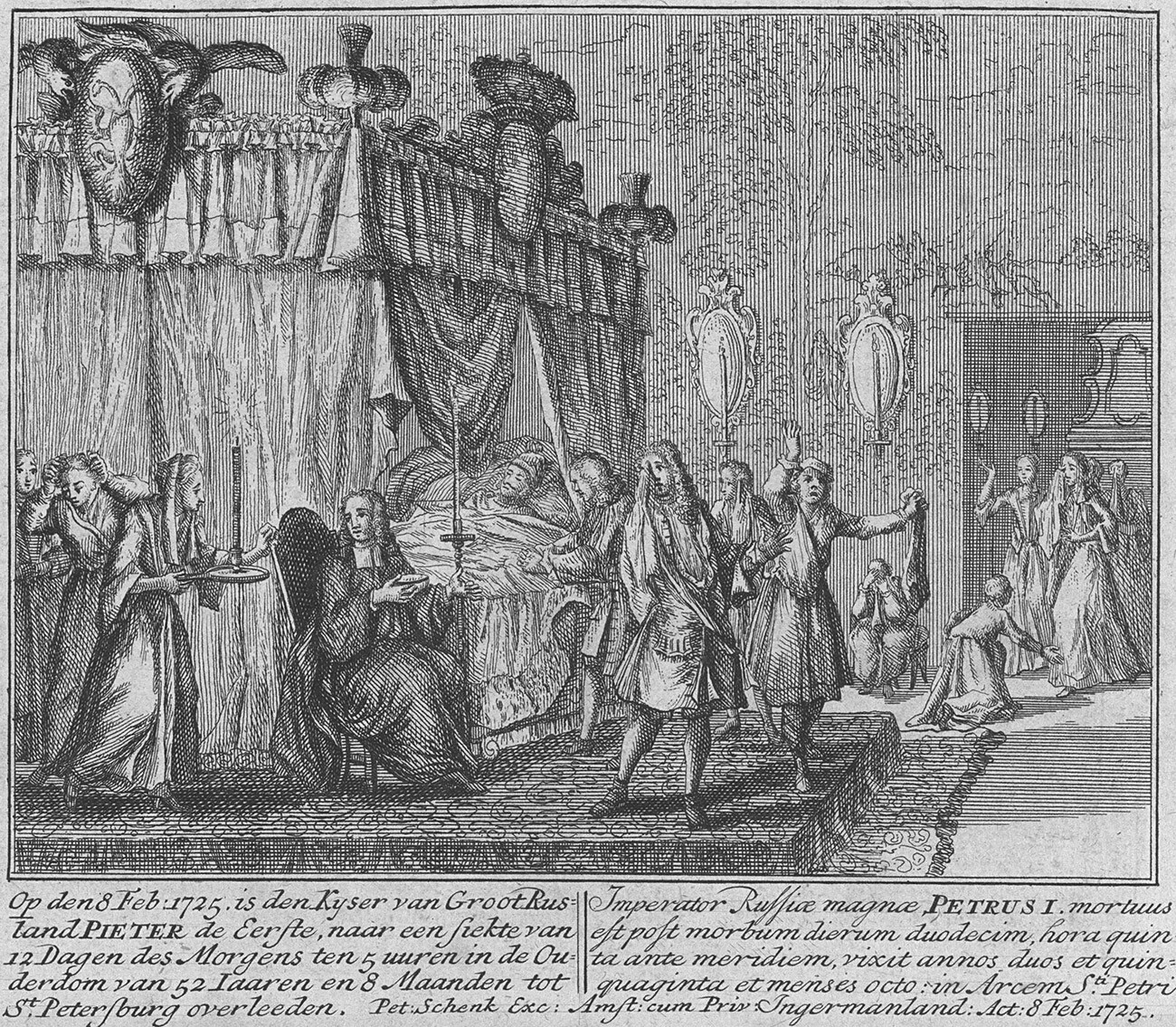

Louis CaravaqueWhen Peter’s final hour came, very precise instructions for his funeral ceremony were prepared. This funeral was unprecedented in its scale.

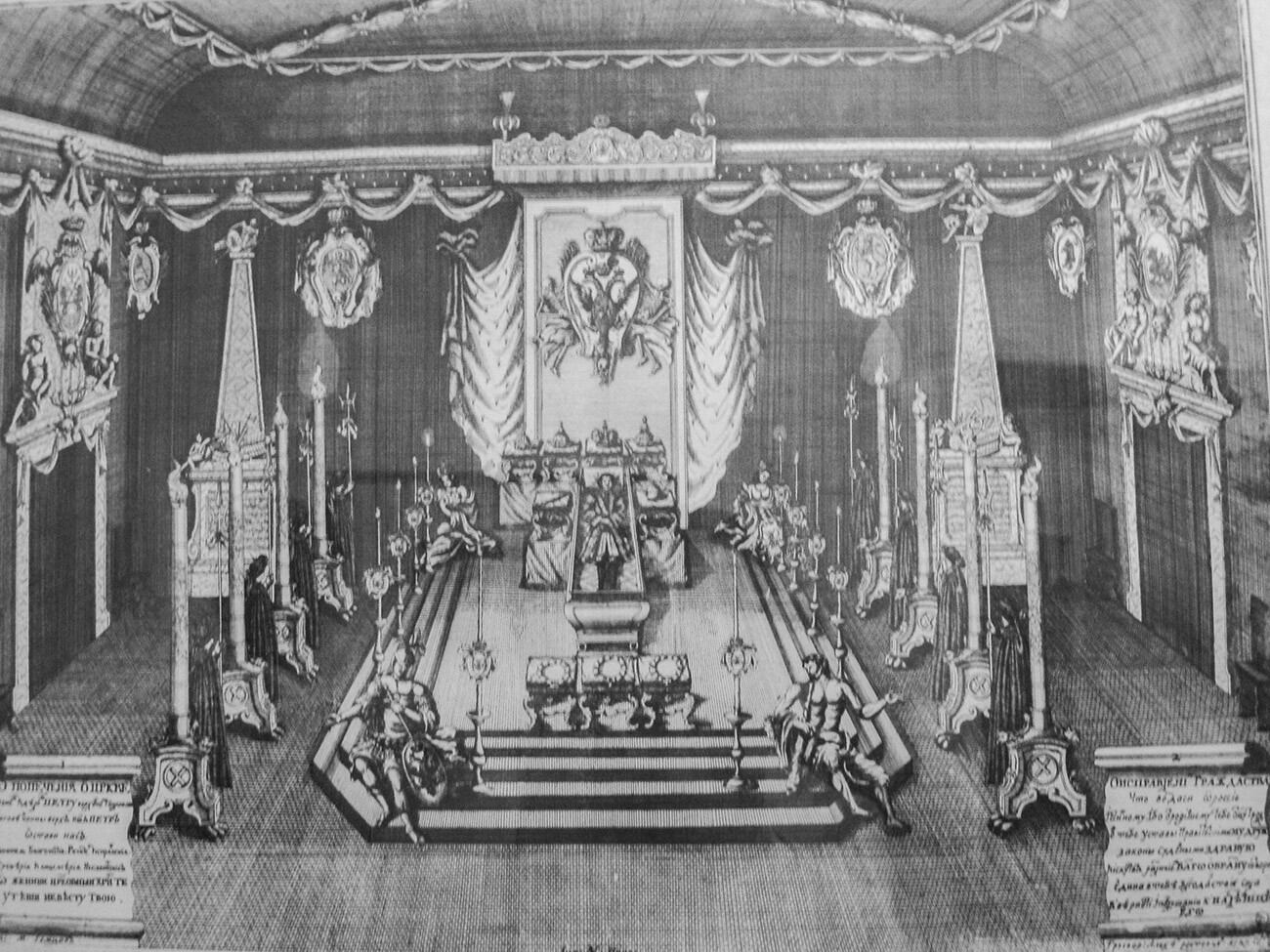

A farewell for Peter the Great was arranged in the Winter Palace. His body was displayed in the specially decorated Mourning Hall (200 square meters in size), draped inside with dark cloth. State symbols were placed around the coffin, along with the tsar’s regalia and medals. The hall was decorated with wooden sculptures. But something was absent – the hall didn’t feature a single Russian Orthodox icon, an unprecedented decision for the time.

And so, surrounded by his regalia and the crowds of people wanting to say their last goodbye to the tsar, his body stayed in the Winter Palace for 42 days. The funeral procession for the tsar to his burial place departed only on March 10. His coffin was carried to the Peter and Paul Cathedral across the frozen Neva River, escorted by an honor guard of 11,000 people. The last farewell was held in the cathedral and still the tsar wasn’t buried afterwards – only a handful of earth was symbolically thrown on his coffin. For six years he remained there, unburied. By that time, Peter the Great’s wife had also passed away – Catherine I, who ascended to the throne after the death of her husband and died three years later. Her coffin, also against the Christian tradition of interring the deceased in the ground, was left unburied next to her husband’s.

Portrait of Princess Natalya Alexeyevna (1673-1716)

Ivan Nikitin/Tretiakov GalleryIt’s quite obvious that such a lengthy farewell ceremony (42 days at the palace) required embalming. That was yet another burial rule changed by Peter the Great: before him, Russian tsars weren’t embalmed. He “rehearsed” this novelty on the body of his beloved sister, Natalya Alexeyevna. When she died in 1716, her brother was abroad. To make it to the farewell for his loved and cherished sister, he gave the order to embalm her body. The process of embalming was carried through successfully. When Peter the Great passed away, the same embalming technique was used, but it went awry.

The problem was that an autopsy on tsars’ bodies was prohibited and Peter the Great was embalmed without an autopsy. And since he died from a purulent inflammation of his bladder, his body already turned black and began to decompose 10 days after death. Despite that, Catherine decided to follow all formalities willed by her husband, including the 42-day-long farewell. Jacob Bruce was in charge of Peter the Great’s embalming process – a close ally of the tsar and one of the best educated people of the time, who gained the reputation of a “dark magician” and nicknamed the ‘tsar’s sorcerer’ among the common folk. The decision not to bury Peter the Great for so long they, naturally, connected to Bruce.

Jacob Bruce’s line belonged to one of the oldest branches of the Scottish Bruce Clan; they lived in Russia since 1647. Among Jacob Bruce’s ancestors, aside from others, was also Robert the Bruce, the king-liberator of Scotland. Jacob Bruce was with Peter the Great back when the tsar was still very young, hiding behind the walls of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius from his enemies and the allies of another political clan. Since then, Jacob never left Peter’s side and became one of his closest associates.

Portrait of Yakov Bruce

Public domainAlthough Jacob Bruce had never studied anywhere, he was actively engaged in self-education through his entire life; he gathered a library of about 1,500 volumes on natural science. He spoke six languages fluently, was well-versed in math, geography, astronomy, optics, mechanics, medicine, military science and other disciplines. Bruce was in charge of Russian book printing; he compiled the Russian-Dutch and Dutch-Russian dictionaries, created the first Russian geometry textbook and opened the first Russian observatory.

This latter fact, most likely, significantly contributed to Bruce’s reputation as a “dark magician” and “sorcerer”. His observatory was located in the Sukharev Tower in Moscow (destroyed in 1934). In Moscow legends, this place was veiled in dark mystery: it was rumored that a secret society of heretics gathered there and, within the tower’s foundation, the “black book” of Bruce was hidden, said to be able to grant unlimited power. It was Bruce, according to folk legends, who “concocted the elixir of eternal youth, created a living doll and flew on a mechanical bird”.

Sukharev Tower

Public domainWhen Peter the Great passed away, Jacob Bruce received the title of High Obermarshal of the so-called Mourning Commission (which was in charge of the farewell ceremony and the funeral procession). He was also the one in charge of the embalming. The fact that the tsar was not buried, the people connected it to the mystical activity of Bruce and his “devilish experiments”. And the more time had passed, the more the public grew convinced that the “tsar’s sorcerer” was behind it.

The truth, however, turned out to be much more prosaic.

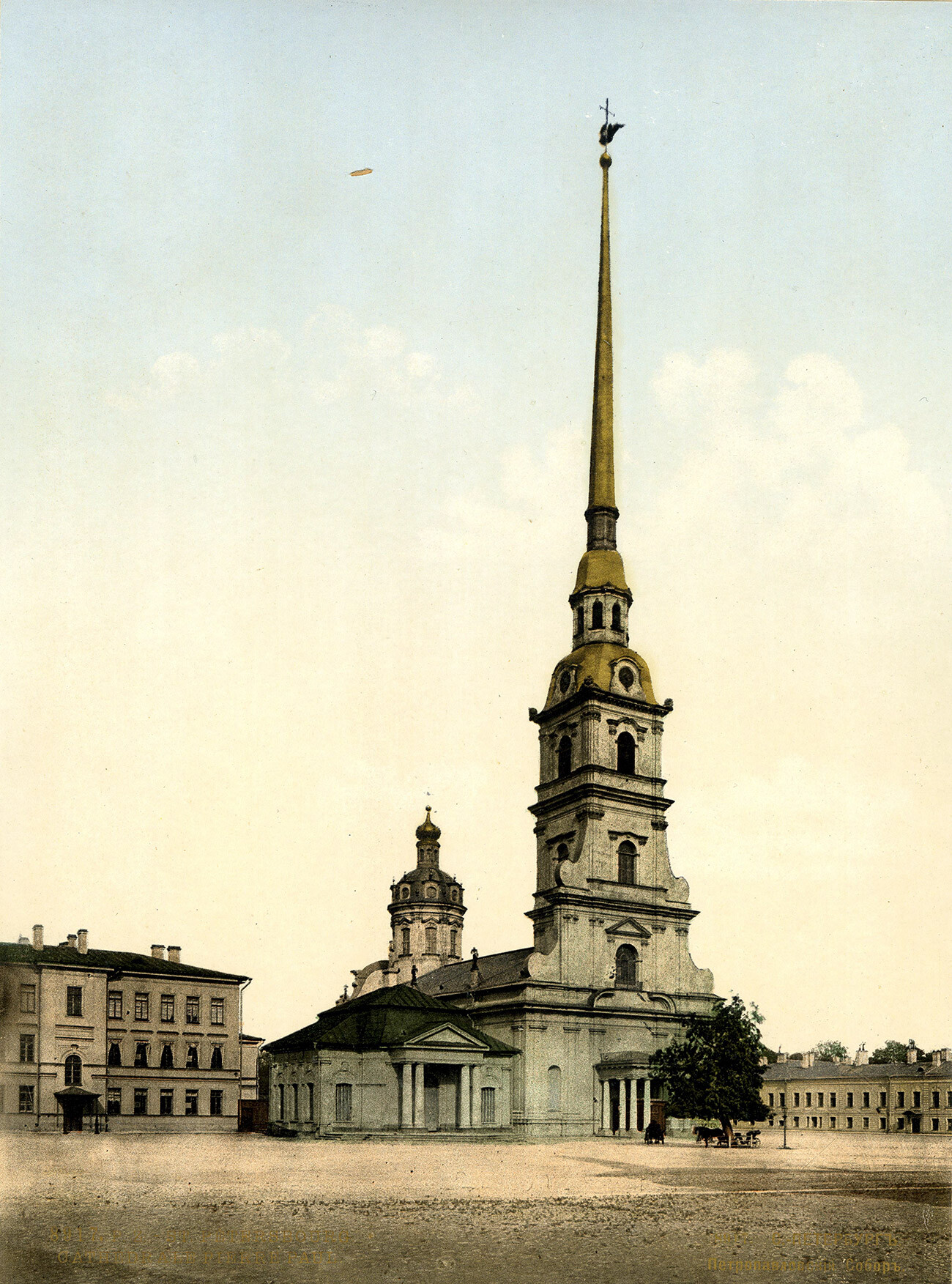

In reality, the final part of the funeral – lowering the coffin into the grave – was delayed to finish the construction of the Emperor’s tomb, as well as the Peter and Paul Cathedral itself. It was located inside the Peter and Paul Fortress – a very special place for the deceased tsar. The date of the fortress foundation – May 16, 1703 – was the founding date of St. Petersburg, Peter the Great’s creation.

St. Peter and Paul's Cathedral in St Petersburg

Public domainWhen Peter the Great passed away, his coffin was placed in a temporary wooden chapel inside the Peter and Paul Cathedral under construction. In 1731, Anna Ioannovna came to power (Peter the Great’s niece) and finally ordered the bodies of Peter and his wife Catherine to be interred. The remains were buried near the southern wall, in front of the Peter and Paul Cathedral’s altar. It’s interesting to note that Peter’s remains were buried in such a way that he couldn’t be exhumed – for that, one would have to tear down the entire cathedral.

Perfektangelll (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Before Peter the Great, Russian monarchs were always buried at different sites: in the Cathedral of the Archangel, in Ascension Convent, in the Cathedral of the Savior on Bor or in Novodevichy Convent. But, as the capital was moved to St. Petersburg, the Peter and Paul Cathedral became the royal tomb.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox