Why did Vladimir Lenin adopt the name ‘Lenin’?

The Bolsheviks relied on fictitious names for conspiratorial reasons. One could simultaneously use several different last names, such was the norm. Real names were never used, be it in the underground or in the press. Vladimir Ulyanov, the father of the global proletariat, had 146: 17 foreign and 129 Russian ones. This was five times what Joseph Stalin had, with ‘Lenin’ being the most famous one, which he used politically and to sign his essays. But Ulyanov never disclosed the reason behind his choice. There are three possible origins for the name.

1) The name of a river, or a Communist Party in-joke

The pseudonyms creed from common Russian names were the most widespread among revolutionary circles. Therefore, the story that Lenin was formed out of the female name ‘Lena/Elena’ is among the most common versions, with the small correction that the name was most likely inspired by the Russian river - and not some woman.

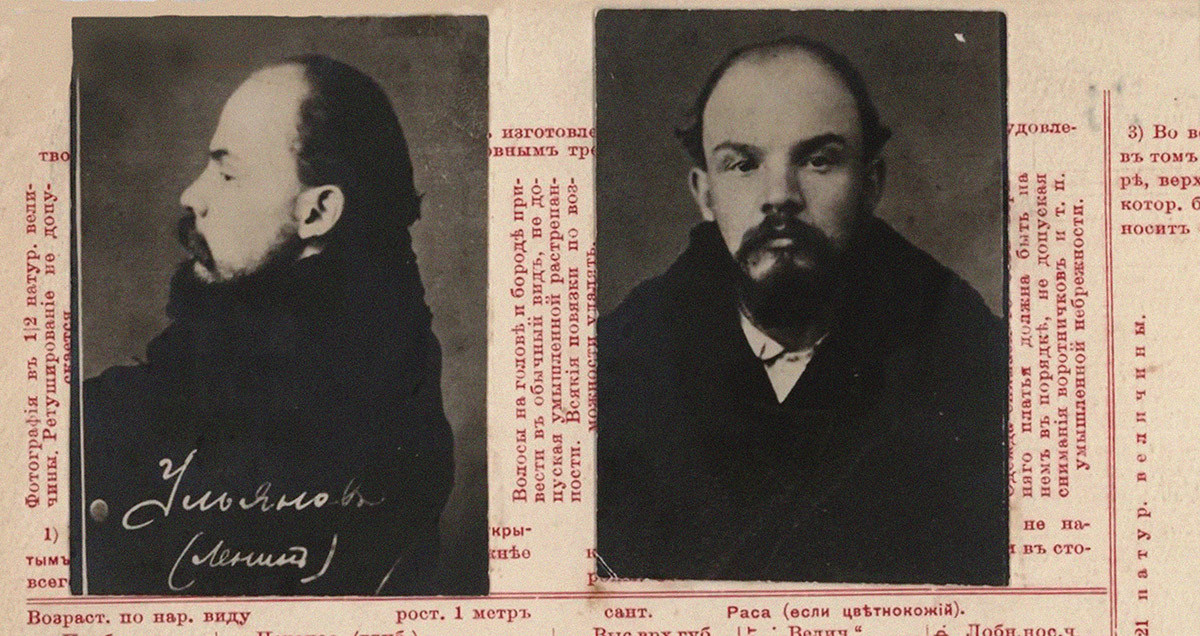

The registration card on Vladimir Ulyanov-Lenin of the Department for Protecting the Public Security and Order, 1895.

Getty ImagesOloga Ulyanova, Lenin’s niece, recalled: “I have reason to believe that… the pseudonym comes from the name of river Lena… Vladimir Iyich did not opt for the name ‘Volgin’ [from the Volga river], as it had been overused at the time, most notably by people like Plekhanov and others.”

It’s possible that the river story is, indeed, the correct one, according to some researchers. However, others also believe that Lenin chose the name simply to poke fun at Georgy Plekhanov - a Menshevik - who relied on the last name ‘Volgin’ quite a bit.

2) It was taken from a dead statesman’s fictitious passport

The first time the Bolshevik leader used the name ‘Lenin’ - or ‘N. Lenin’, to be precise - was in 1901, when signing his essays. The habit stuck and the name became a permanent fixture. This was right around the time a friend of Lenin’s gave him her father’s passport with a changed date of birth: the man’s name was Nikolay Egorovich Lenin. In 1890, Ulyanov had had to leave the country, which required new documents.

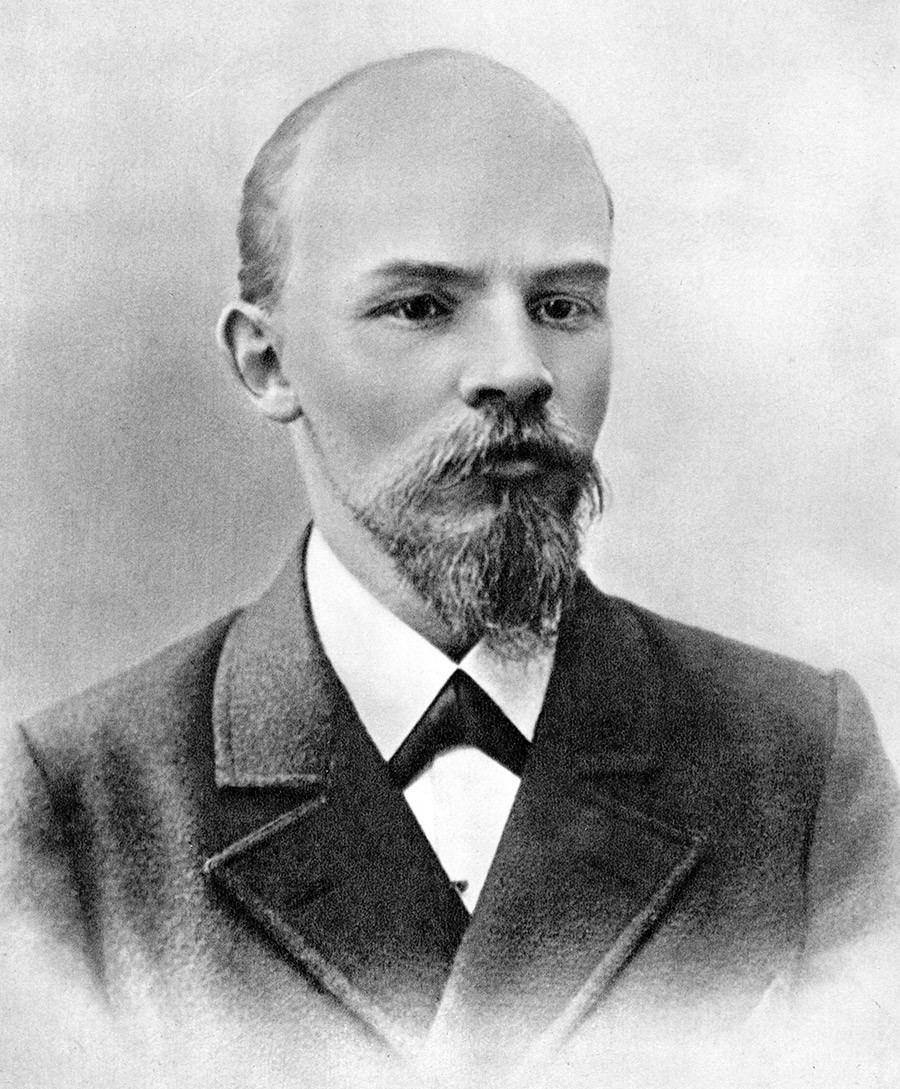

Lenin in 1900.

Getty ImagesHistorian Vladlen Loginov (by the way, the name ‘Vladlen’ is itself formed from the words “Vladimir Lenin”) posits that, having left Russia, Lenin decided to keep the name he received with the new passport. But what lies behind the name itself? Well, the Lenins were nobility - the name was first given in the 17th century to some Cossack, for his accomplishments in the conquest of Siberia, which involved spending the winter on the banks of the Lena. Nikolay Egorovich Lenin - the Bolshevik’s friend’s father - was his descendant, who rose to the rank of state advisor, before retiring and settling down in Yaroslavl Region - or Province, as it was known back then.

Something feels out of place, however: that very Nikolay Lenin died in 1902, a year later than Ulyanov allegedly started to use the name as a party handle.

3) Lenin was a fan of Leo Tolstoy

Vladimir Lenin leaves the State Institute of Pedagogics after a session of the First All Russian Congress on education in 1918.

Getty ImagesThe writer Leo Tolstoy had a novel titled ‘Kazaki’, which talks of a protagonist with the last name ‘Olenin’, who is sent to do forced labor in the Caucasus, where he falls in love with life away from civilization. Lenin loved the works of Tolstoy, while his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, recalled him reading that very novel when he was the one being sent away - to Siberia, in his case. The year was 1898. Tolstoy, according to Lenin, was “the mirror of the Russian revolution”, and, according to historian Aleksey Golenkov, there’s substantial reason to believe that the protagonist’s last name is the true inspiration behind Vladimir Lenin’s famous name.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox