Lady power: How Russian feminists fought for women's rights throughout history

St. Petersburg, 1917. That year, revolutions in Russia started from the rallies in International Women's Day where women protested WWI

SputnikThe idea of feminism, which later would be described ironically as “the radical notion that women are people,” first came to Russia in the 1850s. This was not exactly the easiest time to be an advocate of women’s rights, given how patriarchal and conservative the country was.

Even Leo Tolstoy, who was a humanist, believed that a woman’s purpose in life was to devote herself to her husband and children. He called the women’s rights movement “funny and ruinous, messing up women’s heads” because it argued that women should be allowed to work and seek

First steps

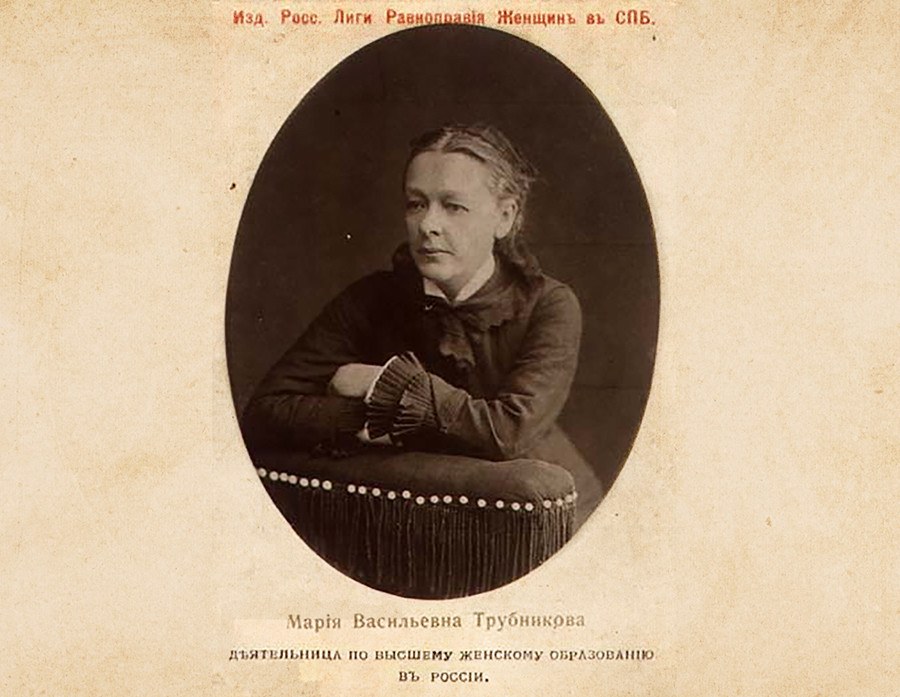

Maria Trubnikova, one among those who helped to provide women of the Russian Empire with higher education and qualified jobs.

Public domainMaria Trubnikova, Nadezhda Stasova

Their hard work paid off, and in 1868 the authorities established the Bestuzhev Courses, which would go on to become the most prominent institute of higher education for women in pre-revolutionary Russia. “Thanks to their efforts, by the beginning of the 20th century Russia ranked among the highest in Europe in terms of women’s higher education,” historian Svetlana Aivazova wrote in Russian Women in the Labyrinth of Equality.

Women of the revolution

Alexandra Kollontai, the main feminist of the 1917 revolution (at least among the Bolsheviks).

George Grantham Bain CollectionAlexandra Kollontai, a Bolshevik leader, formulated her position as “There is no such thing as a separate ‘women’s cause’–women will be free when society is changed.”

Victory and disillusionment

To some extent, this is what happened. Following the February 1917 revolution, women organizations launched rallies and sparked debates in the media, putting

Following the Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917, Alexandra Kollontai was named People's Commissar for Social Welfare, becoming the first female minister in the world. The main “feminist among Marxists,” Kollontai established and worked in the Zhenotdel (a governmental organization supporting Soviet women) from 1919 to 1930. She was also an advocate of the notion of “free love,” meaning here that emancipated women were free to choose and change their partners.

Nevertheless, the euphoria didn’t last long. Under Joseph Stalin, the system turned its attention back to the traditional family. The state banned abortions and suppressed romantic relationships outside of marriage. Additionally, as Svetlana Aivazova explained, “mothers’ function became more complicated…they had to support their families, as one salary wasn’t enough to provide.”

Dissidents and feminism

Natalya Malakhovskaya, one of the main feminist dissidents of the Soviet period, speaking in front of an audience.

Oksana Zamoyskaya“Despite our leaders saying that the Soviet family has no problems, there was violence on the part of men…and the conditions of treatment in maternity homes, in hospitals, were terrible for women,” activist Natalya Malakhovskaya explained in an interview with Radio Liberty. In 1979, she and two colleagues illegally published the Women And Russia almanac to write about issues relating to women in Soviet Russia.

Feminist almanacs and journals were distributed in secret and passed around between acquaintances. After uncovering these circles of dissident feminism, the authorities forced all three main contributors of Women and Russia to emigrate. However, this didn’t completely dash all hopes for equal rights for women in Russia. Feminist ideas continued to exist and made it to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the

For those interested in the current state of feminist ideas in Russia, we have two (1, 2) opposite opinions on whether modern Russia lacks feminism or not.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox